Main Menu

Flyout Menu

The act of actively assisting slaves fleeing from their captors in the South is unequivocally one of the Empire State’s proudest hours.

At a Sunday family luncheon with several middle school relatives and their parents not long ago, the Underground Railroad came up. It was Black History Month, so the topic was very apropos, plus we’re New Yorkers living downstate. Many of the stops of this imaginary railroad were in New York and lower Ontario, Canada, and several of us, me included, had visited them over the years.

What surprised me most about my younger luncheon mates was how little they knew about this important piece of American history. Sadly, our younger family members knew almost nothing about the history of the Underground Railroad; one wasn’t too sure who Harriet Tubman was and a third didn’t realize that the Underground Railroad ended in Canada, St. Catharines to be exact, not Buffalo.

To be sure, that Sunday meal was particularly a lively one, almost like the mythical Reagan Family’s Sunday dinners on the CBS television show, Blue Bloods.

So, we did what most adults would do under the circumstances: we listened to questions and then discussed and explained what we knew about the history of slavery and those heroic people who worked hard to put an end to it. We talked about the dangerous journeys the slaves made to gain their freedom.

And, yes, the kids were interested.

Equally important, the adults decided, we should consider visiting, with them, several Underground Railroad “stops” in New York and lower Ontario either this summer or early autumn. But before that, here’s a summary of what we discussed if you’re considering learning more about the Underground Railroad yourself:

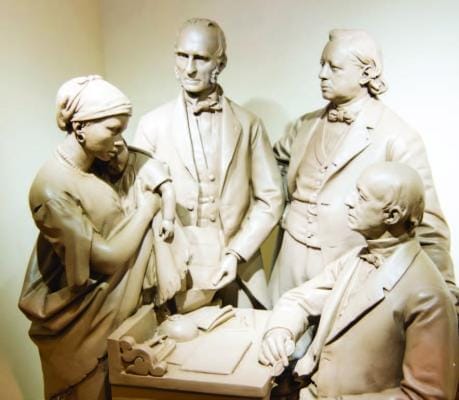

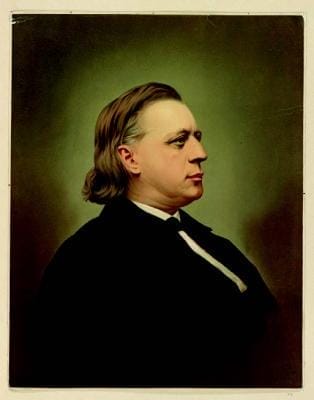

There were “safe” houses and tunnels in and around New York. Perhaps one of the more well-known ones was hidden under the Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims in Brooklyn Heights built in 1847. Harry Ward Beecher was the dynamic minister and abolitionist who preached against slavery here.

Many safe houses were scattered in and around the Hudson Valley. Unfortunately, many of the safe houses here, and in other places were abandoned and demolished over the years, but there are a few remaining sites worth visiting.

Central New York, however, played a key role during those years, and many of the towns along the Erie Canal, from Syracuse and Rochester all the way to Buffalo kept many of the secrets of those fleeing to freedom.

Syracuse, for one, was referred to as a “laboratory of abolitionism, libel and treason” by US Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, and one of the reasons was the so-called Jerry Rescue. William “Jerry” Henry was an escaped slave working in Syracuse when he was arrested in October 1851 under the Fugitive Slave law. He escaped from authorities and was recaptured.

A sympathetic crowd of close to 1,500 townspeople rushed to the building where he was being held. He was spirited out by the crowd and escaped to Kingston, Ontario. Today a marker in downtown Syracuse describes the Jerry Rescue.

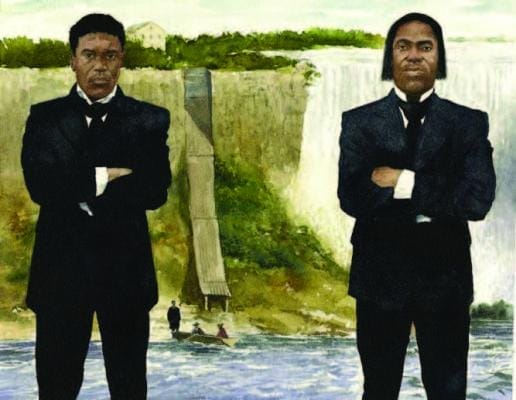

Although many people believe Buffalo was the final stop for the Underground Railroad, it was really one of the last stops before Niagara Falls. From here, slaves entered neighboring Canada by walking across a rickety suspension bridge, took a ferry or even swam across the Niagara River.

Sadly, there are few remains of the important past the cities of Buffalo and neighboring Niagara Falls played in helping slaves flee from the South. There is, however, an African American Underground Railroad trail in and around Buffalo. A highlight is the Michigan Street Baptist Church, one of the Underground Railroad stops for escaping slaves. Today, this church still has some remnants of those hiding places and has low-cost tours of the facility.

In recent years, secret tunnels have been discovered in Buffalo that probably were used to hide fleeing slaves and perhaps were also used to smuggle booze from Canada to the US during Prohibition in the 1920s.

Tubman realized that Canada, where slavery had been abolished by the British Parliament in 1833, should be the destination for slaves seeking freedom.

She moved her base of operations to St. Catharines in southern Ontario, about 50 miles north of the US-Canadian border, where she lived for seven years. Tubman is believed to have made ten trips back to the South during the time, including one in 1857 to rescue her elderly parents in Maryland and bring them to freedom in Canada.

After the Civil War, Tubman moved to Auburn, NY where she worked for rights for women with another firebrand, suffragette Susan B. Anthony.

Tubman died in 1913 when she was well into her 90s. Today, her Auburn home is a national landmark. Not far from it is the Seward House, also a national landmark, the home of William Seward, US Secretary of State, New York senator and governor, abolitionist and a good friend of Tubman.

Although there are many stops along Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor that were home to Underground Railroad historical sites, there are many in New York, too. Here are a few, some of them lesser known, that are reachable traveling on Amtrak and then driving or using public transit, through New York State.

North Star Underground Railroad Museum, Ausable Chasm.

Port Kent Amtrak Station

Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center, Niagara Falls.

Niagara Falls Amtrak Station

Harriet Tubman National Historical Park, Auburn.

Syracuse Amtrak Station

Seward House Museum

Auburn Syracuse Amtrak Station

Oakwood Cemetery of Niagara Falls, Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls Amtrak Station

The Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims, Hicks St., Brooklyn Heights

Moynihan Train Hall Amtrak Station